Okay, buckle up folks. This one is going to be a little boring. I originally thought this would be one essay, but as I got into it, I realized the topic is too complex. I decided to break it into pieces. And there is the operative word” “complex”. Contrary to the nonsense being bandied about today in the media and all over the Internet, impeachment is a very complex process. Because it is so serious, it is important that people understand not only how the process works, but what are the actual grounds to impeach an elected official, in this particular case, the President.

“Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body formally levels charges against a high official of government. Impeachment does not necessarily mean removal from office; it is only a formal statement of charges, akin to an indictment in criminal law, and is thus only the first step towards removal. Once an individual is impeached, he or she must then face the possibility of conviction via legislative vote, which then entails the removal of the individual from office.” (1)

Impeachment is a serious matter. Even more serious when concerning a President of the United States. Impeachment has been used by the U.S. government nineteen times, but only twice for a President (Andrew Johnson, 1868, Bill Clinton 1998). One US Senator was impeached (William Blount 1797). The remaining sixteen impeachments were of judges or cabinet officials.

The Constitution

So, what exactly is the authority for impeaching a President? It’s found in the Constitution, Article 2, Section 4, and reads like this:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

This very small passage gives rise to great discussion which we will attempt to cover, point by point.

First of all, what are “high crimes and misdemeanors”? The Constitution names two of the “high crimes”; they are treason and bribery.

The Constitution is very specific about the definition of treason (Article 3, Section 3, Clause 1): “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.”

The Constitution does not define bribery. It is generally accepted as an official taking money or gifts that influence the official’s behaviors.

The “Misdemeanors” part gets a little trickier. Originally the framers chose the word “corruption”, followed by “maladministration”. Ultimately they settled on “misdemeanors”, a term used in British law that could run the gamut from misappropiating funds, appointing unfit subordinates, not spending allocated money, or even threatening a grand jury. In other words, the very vagueness of the term allowed it to be used by prosecutors to charge almost anything they deemed as an abuse of power as a “misdemeanor”.

Of the nineteen actual impeachment processes since 1797, (mostly judges), the misdemeanors that have been charged included being habitually drunk, showing favoritism on the bench, submitting false expense accounts, making false statements under oath, and other similar charges. Of the eighteen impeachments, only nine resulted in removal of the official. In the remaining cases, the official either resigned or was acquitted.

Presidential Impeachments

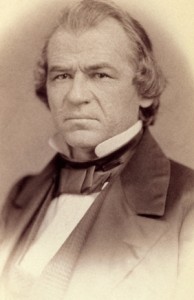

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson was Abraham Lincoln’s Vice President, and assumed the Presidency when Lincoln was assassinated in 1865. Johnson, a Democrat, had immediate problems with the Republican-dominated Congress during reconstruction. Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act, which required Johnson to receive Congressional approval to fire any member of the executive branch who had been approved by Congress. Johnson believed the Act was unconstitutional, and responded by firing the Secretary of War, a Republican. Congress responded by passing eleven articles of impeachment, including sending orders through improper channels and conspiring against Congress. In the Senate, only three charges were brought, and he was not convicted.

The case against Andrew Johnson seems clearly a partisan political attack, with little substance, giving some insight into just how nonsensical articles of impeachment can be.

Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton’s problems began when a special counsel was appointed to investigate Whitewater, an Arkansas land deal that Clinton had participated in twenty years earlier. In a good example of the “reach” of an appointed special counsel, the investigation expanded to include the firing of White House travel office staff, the misuse of FBI funds, and Clinton’s affair with Monica LewInsky. The House Judiciary Committee presented eleven impeachable items, all related to the LewInsky affair. The Committee voted four articles of impeachment, including perjury before a grand jury, obstruction of justice, and misusing and abusing his office. Clinton was impeached, but not convicted by the Senate.

Some people believe that Richard Nixon was impeached. He was not, and avoided impreachment by resigning from office.

The Process of Impeachment

Impeachment proceedings begin in the House Judiciary Committee. Any bills of impreachment are referred to this committee. As part of the Judiciary Committee inquiry, the Committee may collect evidence, hold hearings and hear testimony of relevent witnesses. Typically the committee has both a majoriy and minority counsel, one for each party. If grounds for impreachment are found, the Committee formulates the Articles of Impeachment. The committee then votes on the articles, and if passed, they are referred to the entire House of Representatives, which then debates the issues.

If Articles of Impeachment are approved, the House appoints managers, who act as procescutors for each article. A hearing on the matter is held in the Senate, with the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court as the presiding official. The hearings are conducted as a trial, with witnesses and testimony. The defendant is entitled to legal counsel, and may cross-examine witnesses. At the conclusion of the hearing, the Senate debates the issues in private. A two-thirds majority is needed for a conviction and removal from office.

The entire process can be quite lengthy. What follows is the timeline of the Clinton impeachment:

January – August 1994: Attorney General Janet Reno appoints Robert Fiske Jr. as special prosecutor in the Whitewater Investigation. He is replaced by Kenneth Starr in August.

January 1998: Starr receives permission to expand his probe to include the Clinton/Lewinsky relationship.

September 1998: House of Representatives receives report from Ken Starr (3183 pages of testimony and evidence).

October 5, 1998: the House Judiciary Committee recommends a full impeachment inquiry.

November 19, 1998: Starr presents his case to House Judiciary Committee

December 11, 1998: House Judiciary Committee approves three articles of impeachment.

December 19, 1998: House of Representatives approve two articles on impeachment.

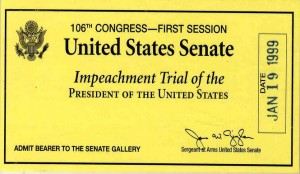

January 14, 1999: Trial begins in Senate

February 9, 1999: Senate begins closed-door deliberations.

February 12, 1999: Clinton acquitted.

So this is the basic process. In future articles, we will discuss more current issues, especially how they may relate to President Trump. Inasmuch as the media seems to have caught impeachment fever these days, it is likely there will be much to discuss.

References:

(3) Presidential Impeachment Legal Standards

(4) Alan Dershowitz Unitary Theorty of the Executive

Constitutional Rights Foundation High Crimes and Misdemeanors